Written by Steve Compton – Coordinator of the Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation.

The Bunurong People are the Indigenous People from south eastern Victoria. Their traditional land extends from the Werribee River in the north-west, down to Wilson’s Promontory in the south east, taking the catchments of old Carrum swamp, Westernport Bay and the Tarwin River, and including Mornington Peninsula, Phillip Island and French Island.

Bunurong People are part of a language group or nation know as Koolin. Bunurong People prefer to be known as Koolin rather than Koori, which is a word from a different language. The Bass Coast Shire is within the clan estate of the Yalloc Bulluk Bunurong and the Lowandjeri Bulluk Bunurong.

The Yalloc Bulluk Bunurong

The Yalloc Bulluk are one of the largest clans of Bunurong People. Their traditional land took in the eastern catchment of Westernport Bay, also the catchment of the Powlett River, French Island and Phillip Island. The Yalloc Bulluk, along with other Bunurong clans, the Burinyong Bulluk of Mornington Peninsula and the Lowandjeri Bulluk of the Tarwin River, were some of the first Aboriginal People in Victoria to make contact with European mariners and there are many documented accounts by these early mariners in archives all over the world.

An example is the journals of Durmont D ’Urville, commander of the French ship the L ’Astrolabe, who in 1826 records his visit to Westernport Bay and reports seeing sealers, their Aboriginal wives and children. He also visited a Yalloc Bulluk village around where present-day San Remo now stands, here he reported that there was over 50 to 100 huts.

Like most other Indigenous Peoples, Yalloc Bulluk People changed with the seasons. Though a seasonal change didn’t always mean a move to another camp, it almost always involved a change in diet as certain resources become abundant and others faded until the next season.

During the warm summer months, the Yalloc Bulluk would make bark canoes and visit French Island and Phillip Island to catch seal and mutton birds. Other days would be spent foraging the Westernport Bays many tidal flats or the rocky platforms of the Bass Coast for their favourite shellfish, or perhaps fishing for snapper at the mouth of one of the many mangrove inlets that run into the northeastern side of Westernport Bay. A part of everyday was the 1-2 hours spent harvesting indigenous vegetables and fruits such as orchid bulbs or wild currents.

As summer came to an end the Yalloc Bulluk would begin making cloaks and rugs from possum and kangaroo skins, and collecting the flower stems of the grass tree, which was a favoured timber for making fire, and steeped in lore. The Yalloc Bulluk needed these things to survive but they would quite often make or collect a little extra for trade or as a gift for friends or family unable to get their own.

In winter, the Yalloc Bulluk would meet with other Bunurong clans or Koolin People at their favourite hunting grounds in the Dandenong, Bass Valley and Upper Powlett River. Here the People would co-cooperatively hunt kangaroos, wallabies, emus and possums, dig out wombats and snare small. marsupials. They would catch eels and fish from the many creeks and swamps, and also harvest yams, the pith from the tree fern and Cumbungi. They would also collect the many mushrooms that grew in the damp weather.

The Yalloc Bulluk would also take special trips to the Gurdies to catch lyrebirds, whose feathers where prized for ceremonies and had spiritual significance; they would of course eat the bird.

As winter began to shy away from’summer, the elders of the Yalloc Bulluk would see the first blooms of the Ti-tree and declare it was once again time to travel back to the swamps and coastal lagoons for the egging season, when thousands of wading and aquatic birds would begin to nest and lay their eggs, ”swan eggs being the favoured type, and strict collection and management protocols applied to the harvesting of this much anticipated resource.

The Lowandjeri Bulluk Bunurong

Lowandjeri Bulluk traditional land takes in the catchment of Anderson’s Inlet, the Tarwin River and Waratah Bay; it also included Wilson’s Promontory, Cape Liptrap, the Glennies Group and the Anser Group of Islands. The Lowandjeri Bulluk get their name from a Koolin creation being whose name was Lowan. Lowan was said to rest at Warmoom.

The Lowandjeri Bulluk were most likely the first Aboriginal people in Victoria to make contact with European mariners and explorers, unfortunately this contact was to be all bad for the Lowandjeri Bulluk.

The Lowandjeri had for millennia, maintained amicable relationship with the Gurnai from East Gippsland through. trade, ceremony and a balanced population to defend their customary and hereditary rights. The impact of early sealers and whalers on the Lowandjeri Bulluk population through abductions and murder was devastating, and by the 1830’s the Lowandjeri Bulluk were unable to defend themselves against the Gumia’s superior numbers. By the 1840’s, the last few surviving families of Lowandjeri Bulluk made their way to a very young Melbourne to be among the other Koolin tribes assembled there.

During the warmer months of the year the Lowandjeri Bulluk would visit ceremonial grounds at places like Anderson’s Inlet, Cape Liptrap and Wilson’s Promontory to name a few._While at these locations, they would access the many coastal resources at their disposal, such as crayfish, shellfish, fish, seal and the dependable mutton bird. To balance their diet they would gather seed for flour and collect vegetables such as yams and orchid bulbs, while the children ate bush fruits such as the wild raspberry and the kangaroo apple.

As warmth gave way to early morning fogs, the Lowandjeri knew it was time to begin preparing possum and kangaroo skins to be made into cloaks and rugs for the coming winter. Unlike other Bunurong clans the Lowandjeri Bulluk didn’t have to prepare cloaks’ or rugs for trade, instead they traded greenstone from an ancient quarry on Lowandjeri land. Greenstone is a highly prized stone for the making of stone axes; the stone had the right balance of hardness, weight and an ability to maintain a sharp edge.

As the season changed so did the Lowandjeri, as winter drew nearer the Lowandjeri would begin to move inland to live off the abundant game, They would ambush Emus and Bush Turkeys (Australian Bustard, now extinct locally), hunt kangaroos, net birds and snare small game such as bandicoot’s and potoroo’s, others would harvest the tubers of the water ribbons and the pith from the tree ferns, while the children collected wattle gum or searched for wild honey for something“ a little sweet to eat.

Some Lowandjeri Bulluk families would travel to camps around Korumburra and Poowong to spend winter with families from the neighbouring Yalloc Bulluk Bunurong. From here they would make excursions to ceremonial grounds in the nearby mountains. At these camps the elders were able to, pass on valuable cultural and spiritual knowledge to the younger people. Then as the first of the wattles bloom the elders would know it was time to make their nets and begin their trip to the coast for the diverse and plentiful supply of fish that was easily caught with their low strong nets in the shallow inlets and bays. Then, once again, the season would end and another begin.

There is much more to Bunurong life, and any one who has spent enough time in their land will see the diversity in their available resources and this is looking at only what has been spared from development and exploitation for the moment.

Today the Bunurong have little access to their traditional land, and actively struggle for the recognition and protection of Bunurong culture, heritage and their cultural environment through the Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation.

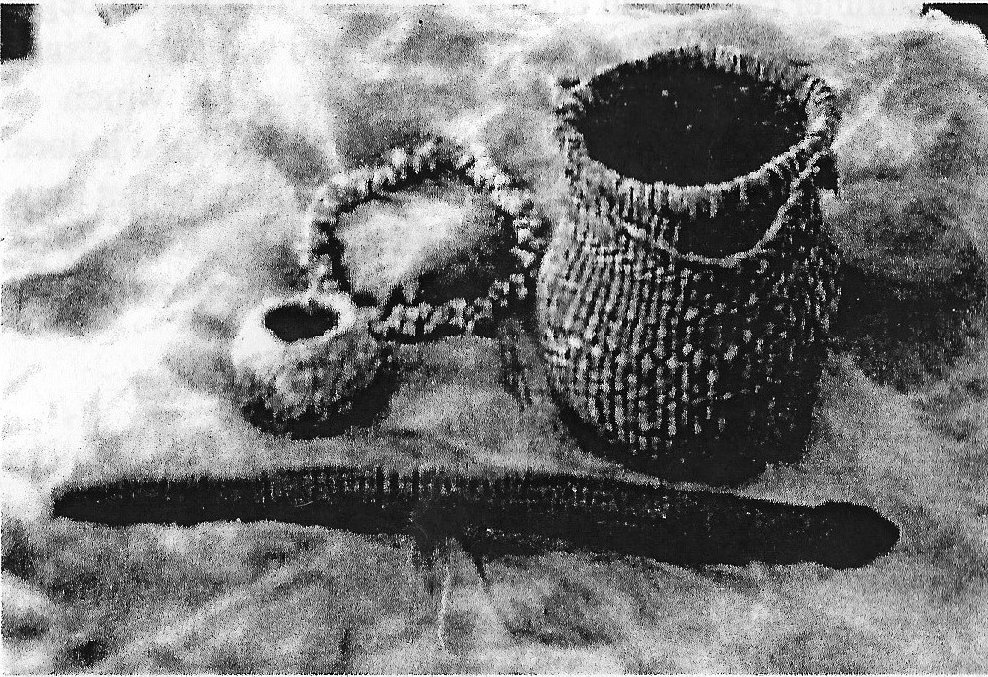

1.Beenyac basket made from spiny mat rush, by Bunurong elder Lenah Newson. Used for collecting berries.

2. Small basket is made from raffia and wool with mutton bird feathers by Lenah Newson for her grand-daughter.

3. Wooden throwing stick made from wattle, incised with a kangaroo tooth. Used for catching small marsupials – a woman ’s tool.

4. Shell necklace made from local shell. Used for trade.

5. Display cloth is silk dyed with eucalypt by Lenah Newson.

Source: Reproduced from a 2 page leaflet titled “The Bunurong People written by Steve Compton” available from Bass Coast Shire information centres.